Dripping wet with baptismal waters from the Jordan River, Jesus moved into the wild—the wilderness—led by the Spirit. This was not an REI wilderness experience. No waterproof jacket, sun-repellent shirt, nor hiking shoes. No brim on his hat. Not even a protein bar in his pocket… no food nor comfort in the wilderness. It was Jesus and the devil and little else.

Oh, but there was the wilderness. Jesus went into the wilderness—a place thought to be full of wild beasts and demons; of roaming and tormented spirits; the dangerous meeting place of God and frail human beings; the strange abode of ministering angels. Here the devil prowled like a roaring lion seeking souls to devour. And the Spirit dwelt with Jesus.

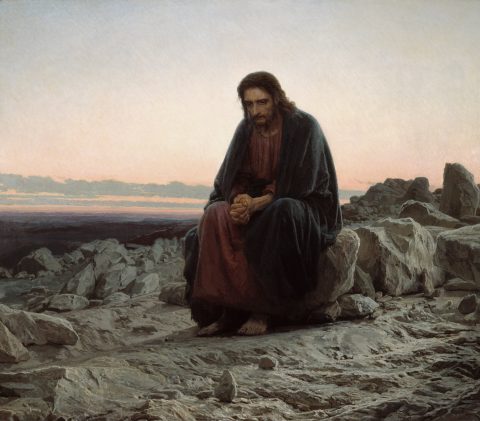

I’ve been looking this week at paintings on the theme of Jesus in the wilderness. Most show him in a bleak uncomfortable, foreboding landscape. During our Lenten Taize service this next Thursday (where I hope to see you,) we are going to meditate for a time on one of those paintings: Christ in the Wilderness by Ivan Kramskoi. Jesus sits, atop an ample stone, in the midst of a pallid, rocky desert. Light from a pastel sky reflects off the scene, but in spite of it, the mood of the painting is quite dark. Jesus’s face depicts a troubled man. He may be wrestling with God, or tempted by the devil, or just plain hungry, and he’s there in the wilderness where he has no access to the things in his life on which he has come to rely. In gazing at that painting, it would be easy to think that the difficulties for Jesus were due to the environment around him. The rocks and sand and grit and darkness are not inviting. However, Jesus’s difficulties came not so much from heat nor desert nor wilderness. No, the temptations that Jesus faced are tendencies inside every human being, and they can appear in any landscape.

The wilderness isn’t just a place in nature with few creature comforts. Wilderness is often seen as the places on earth that have remained pretty much untouched by human hands, human development; wilderness, we think, is an uncultivated, uninhabited and inhospitable region. So, while many of us say we have little to no experience in the areas on our planet that have not been touched by human hands, almost everyone can say they have been to the wilderness… that place of inhospitality.

It is likely that the wilderness that you have been to didn’t look like the forest, nor the desert, nor the bleak wastelands. Maybe the wilderness that you’ve experienced looked more like a substandard motel that you once had to go to because there was no other place you could go; or maybe it looked like the hospital waiting room where you seemed to wait for an eternity for someone—anyone—to come and take care of you or your loved one. Perhaps the wilderness looked like the parking lot where you left your car on the day your life changed due to the end of a relationship, and you were in so much shock and grief that you couldn’t find your way back to the car. Or the wilderness could have been that time that you had to give some difficult news to someone you loved and you struggled to find the words. These, too, are examples of wilderness. The place where there is no comfort—or at least that is how it seems. It is the place where you look around you and see nothing that is familiar or available for your usual comfort.

In these wilderness experiences, one feels a sense of vulnerability, a sense of doubt…Can I really deal with this discomfort? I don’t know if I can do it. And temptations buzz in our minds… If I just made some other arrangements, I could get out of this. If I could just do this one thing, I could leave this wilderness time and go back to feeling safe, comfortable, and cared for. Being in the wilderness and facing temptations is not for the faint of heart. Most of us do our darnedest to steer clear of the it.

Ladislaus Boros, a Hungarian Roman Catholic theologian and priest, wrote this about Jesus’ temptation:

“The temptations were intended to induce him to externalize his being, to turn his life into an expression of power, to dominate, to be “extraordinary”; and not, on the contrary, to hold out to the end, enduring whatever was to befall him, hiding his immediate personal divinity in the obscurity of his way of life, not imposing himself upon anyone, living cheerfully and peacefully among simple people, and not forcing God’s hand even (in) his most extreme need.

"When Christ rejected the temptations, he won back the essence of humanity. He let the powers of evil come right up to him. And at the decisive moment he shattered them with a simple No. He did not betray us for a crust of bread. To him our wretchedness was sacred. He did not hesitate for a moment. His victory was not a dazzling triumph, since no one knew of it. It took place in utter solitude. Nevertheless, it made possible a new future for mankind—the turning of hearts to goodness, not of stones to bread.”[1]

Stones of all sizes and shapes fill the landscape of Christ in the Wilderness, the painting I spoke of. If Jesus had taken the challenge from the devil, and turned even one stone into bread, perhaps he could have done the same with the abundant stones that cover Israel’s landscape. He could have turned those stones into ample food to feed the many hungry people in a land often wracked by famine. Perhaps he could have become a new Moses for the people. But Jesus’s reply drew on Moses himself, by citing Deuteronomy 8:3: “One does not live by bread alone.” Bread is good, particularly to a famished man, but it was not sufficient to define Jesus’s mission. Instead, Jesus gave to God the obedience and trust that Israel had failed to give.

The abundant stones in Kramskoi’s painting present a landscape of materials that could be used either for building up or for blocking out something. Etty Hillesum, a Jewish woman and peace activist who lived in Amsterdam during the Nazi occupation, and who must have regularly experienced the fear and vulnerability of the wilderness during those years, wrote this in her diary: “There is a really deep well inside me. And in it dwells God. Sometimes I am there too. But more often stones and grit block the well, and God is buried beneath. Then he (God) must be dug out again.”

Those pieces of stone and grit that block the well are often the things we use to take away the worry, the doubt, the fear… things we rely on to make us more comfortable… things that might not be good for us, and God reminds us of that, though sometimes we do not listen.

During Lent, you and I, siblings in Christ, are invited on a trip into the wilderness to identify the grit and rocks and bits that fill the space where only God is—and to remember that space is God’s alone. It is a time to discern our own temptations and to be aware of how we often fill the hole that belongs only to God. It’s time to get rid of some of that grit and gravel, and it may be in taking on something that will keep the opening ready only for God—perhaps a new spiritual practice or some newness that feeds us spiritually. Lent’s slowness invites us to identify the distractions in our lives… the things we reach for when we are too tired, too sad, or too afraid to enter the wilderness of the present moment, OR too tired or sad or afraid to even remember that we do not go alone into that wilderness. We go with the Spirit who abides with us.

Journey into the wilderness during Lent’s forty days to face your fears, your doubts, your vulnerabilities, your temptations—all the things that take the place of God in your life. You don’t have to pack anything, though I expect you, like I, already have. And the Spirit will dwell with us the whole time.

[1] Boros, Ladislaus, In Time of Temptation (translated by Simon and Erika Young)